Classroom Routines and Student Jobs (part 2)

At the end of every school year, I (try my best to) reflect on which classroom routines worked best, which did not work at all, and which I can improve or alter. Very often our routines grew out of necessity, as has been the case in the past couple of years of pandemic education; however, an “organic” routine doesn’t automatically guarantee its usefulness, particularly for a neurodivergent learner. One question I use during while reflecting is: what purpose does this routine serve? Or more specifically: what purpose does this routine serve in facilitating language acquisition? Trying to be intentional with the selection and implementation of routines is critical to their effectiveness.

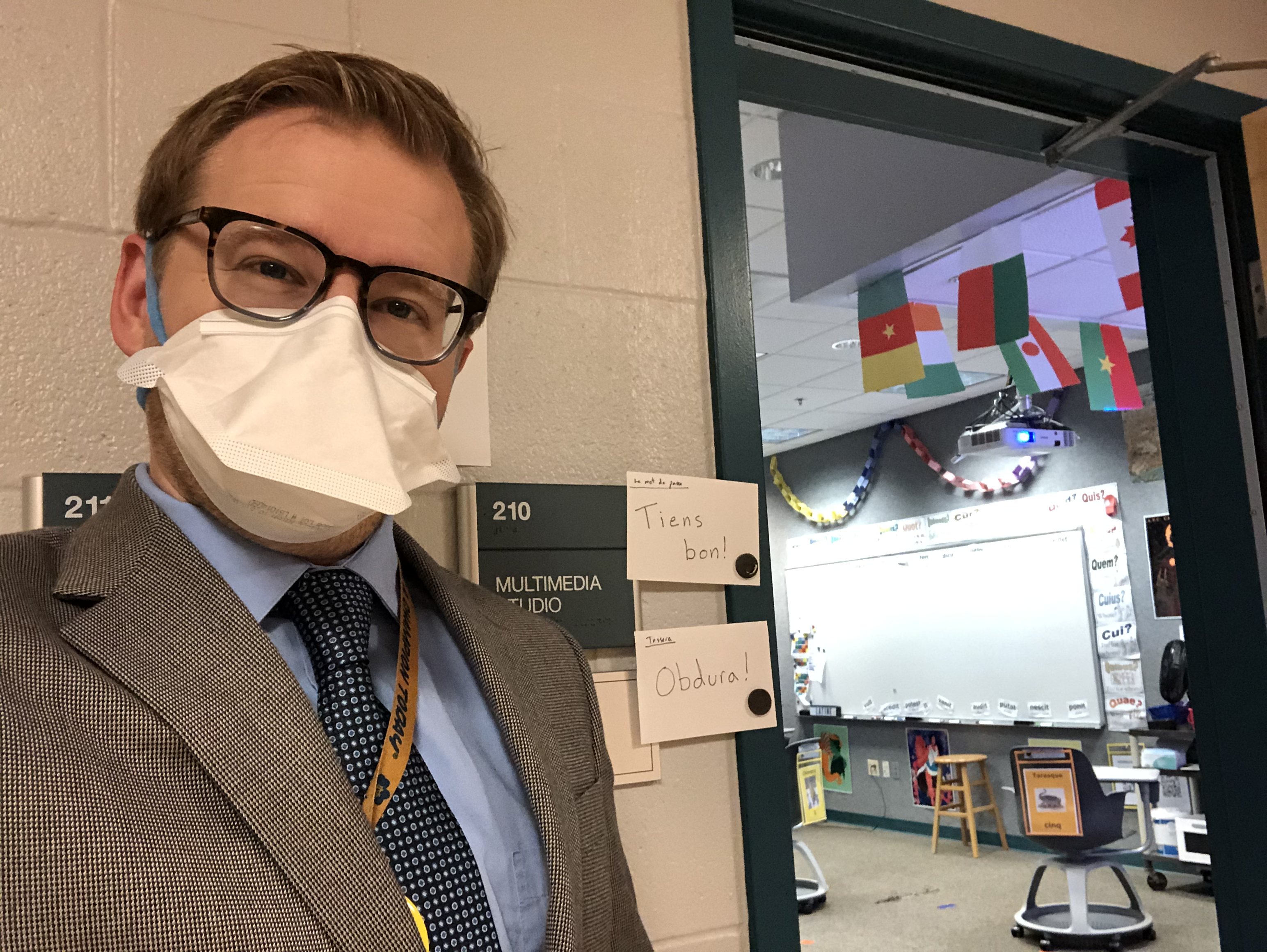

My class always starts before class starts — at the doorway with a password. I can’t remember from whom I first stole this activity (apologies and thanks whoever you are!), but I’ve been doing class passwords/tesserae/les mots de passe at the door for the past four years, including online during remote/hybrid learning. What started as an extra attempt at target language exposure turned into something infinitely more useful. You have probably heard about passwords or even used them yourself. For my classroom, a typical procedure works like this, with a lot of room for flexibility and individual options:

Liminal Password Procedure

- On the first day of the week, I post a sticky note or notecard outside the door with a new word or phrase. Think: “Carpe Diem” or “Quoi de neuf?”

- Students take their time to sound out the words, and I am there to support them. Upon successful utterance, they are allowed in. For more conversational passwords, a conversation in the target language often takes place.

- Upon entry, students immediately see the agenda, materials needed, and expectations for the day. They are expected to be ready by the start of class.

- In class on that first day, one of the agenda items is the password itself. At that time, we discuss the password, see if anyone has heard of it before, and explore the original context as necessary. Pro-tip: Tongue twisters are always a “fun” choice, e.g. “Ō Tite tūte Tatī tibi tanta, tyranne, tulistī!”

- On the following days, the sticky note with the password is moved from outside the doorway to inside the threshold. Students are allowed to “cheat” by taking a peek as necessary. By the end of the week, the sticky note is removed entirely, with the expectation that students are prepared to share it.

- OPTIONAL STUDENT JOB: A greeter/bouncer at the doorway to ensure adequate password sharing. I have personally found more success at younger ages with this particular job. Additionally, this role should never be forced in my experience as not everyone can feel comfortable with it.

Embracing Flexibility for Greater Buy-in

This past year, I have been even more flexible with how the password interactions take place because I find it helps all types of learners; my prior rigidity only served myself and not those I was trying to reach. For instance, I have seen some students whip out a sticky note or even their speech-to-text on their phones to share for them, which I thought was brilliant. Also as a result of safety considerations for the pandemic, I have stopped standing in the middle of the doorway for the interaction; now, I stand just to the side of the doorway in the hall, which allows some students to simply say the password while walking by. No forced conversation, no unnecessary eye contact, which allows them to feel more comfortable with me.

By the way, if a student forgets, they almost always are quick to run back and share the phrase. Why? I suspect that they know how important it is to start on the right foot. No matter the learner, having time to transition between spaces is critical. How many times have you awkwardly forgotten why you walked in a room once you’ve crossed the threshold (or limen, in Latin)? That’s a real thing by the way — when I was an undergraduate, I was a test subject for my Psych 101 course. They published the results: fascinating stuff! In any case, providing that first step can be the difference between a student feeling comfortable and ready or feeling lost and behind.

No matter the learner, having time to transition between spaces is critical.

From there, the start of class transitions are more or less the same every day in the target language: 1) Hello, everyone!; 2) Who is absent?; 3) How are you?; 4) Please look at the agenda if you have not already — What questions do you have about what we are doing today?. Even for these questions, notes are acceptable and welcome forms of communications. (Side note: I must say, there are times where I do miss the chat box of the online classroom, as many students felt more comfortable using that as their voice. Since moving back into the physical classroom, I have worked to provide alternative means to communicate, such as a Padlet “parking lot”, but an email sent post-class remains the most popular option for those students.)

P.S. This activity has a wonderful, unexpected side effect. Many students who are not taking French or Latin have had FOMO and actually give the password to try and gain entry. We politely shoo them away but encourage them to take our languages next year. Low effort recruitment tool? Yes, please!

How do you start your classes? What purpose do your first routines serve? Please email widernetlang@gmail.com and let us know!

[Did you miss part 1 of this series? Check it out here: “It Takes a Village”]